…and dear reader,

They aren’t always scary.

The book I’ve spent so many months working on can’t be released in India — because Kindle said it isn’t appropriate for the Indian market. I made it for the Indian market, so I can’t pretend I wasn’t disappointed.

But something about the place I’m in, tells me that life has its own rhythm — and I’ve decided to let it lead me.

I’ve written back to Amazon, though I know I can’t contest their decision.

Anyway, it may not be searchable yet but here are the links:

For US | UK | DE | FR | ES | IT | NL | BR | CA | MX | AU |

So, the book won’t be released in Japan and India — a real setback, and not at all how I imagined things would go. But here I am, looking at life and saying: Show me your plan. I’m ready.

This, of course, comes after trying to reason with the Kindle team — who reply to me like bots.

Today, I had signed up for a walk through Hasnabad. The Hasnabad Dargah — often called Mumbai’s "Mini Taj Mahal" — is a 19th-century marble mausoleum in Mazgaon, built by the Khoja Shia Ismaili community to honor Aga Khan I.

Though I really wanted to go, I wasn’t sure I’d be up for an early start. Just yesterday, I even offered my ticket to three different friends, unsure if I’d make it. I decided to leave it up to how I felt in the morning.

At 5:50 a.m., I woke up to turn off the fan — and in that moment, I decided to go. And I’m so glad I did. It was absolutely the right decision.

Hasnabad is usually not open to the public, but today — thanks to Asiatic and the Khoja community — we were allowed in. The walk was fantastic. The guide was delightfully funny, philosophical, and openly vulnerable, which made the experience even more memorable.

Hasnabad is located in a place called Anjeerwadi — named after the fig (anjeer) trees that once grew abundantly in Mazgaon. We learned about the famed Mazgaon mangoes, which were so prized by the Mughals that they stationed a garrison to protect them. There’s even a neighborhood in Mazgaon called Ambewadi, named after these mangoes, the cultivator has been lost, I am told.

They also pointed out how, along a single street, you can find cemeteries belonging to Iranian Shia Muslims, Khoja Shia Muslims, and the Bene Israel community — a striking symbol of Bombay’s diverse history. I was curios and wanted to go.

Just as the official walk ended, we heard that Rafique — a journalist and historian of Bombay — was willing to take us on an impromptu walk to the cemeteries. So, of course, we all went along.

At the Iranian Shia Muslim cemetery which was very green, he showed us the tomb of Meena Kumari and Kamal Amrohi. Meena Kumari’s tomb smelled of roses.

I also saw this nazm about a father.

At the Khoja Shia Muslim cemetery he pointed us to the tomb of Ratanbai, the wife of Mohd Ali Jinnah.

After that, Rafique wanted to eat, and a few of us joined him. Eventually, it was just the three of us — him, Uzma, and me. I had exchanged only a few words with each of them by then, so really, it was three strangers sitting at a table but he regaled us with many tales and we were very much at ease.

We ate at Sarvi — a restaurant famously frequented by the writer Saadat Hasan Manto. On the way there, Rafique mentioned how he’d like to give us books someday.

After the meal, Uzma agreed to walk with me to a little hillock I’d been eyeing from the Dockyard Road train station for years. I didn’t know it was called Mazgaon Hill but she told me how, back in the day, the sea reached up to the hill, and how a married British woman had once escaped from there. I was thrilled — not only was she willing to explore the place with me, but she also had stories to share about it.

But by then Rafique asked if we’d go home with him as he had books to offer us. Uzma said she wouldn’t have gone if I weren’t there; I said the same. So, we took a cab to his home.

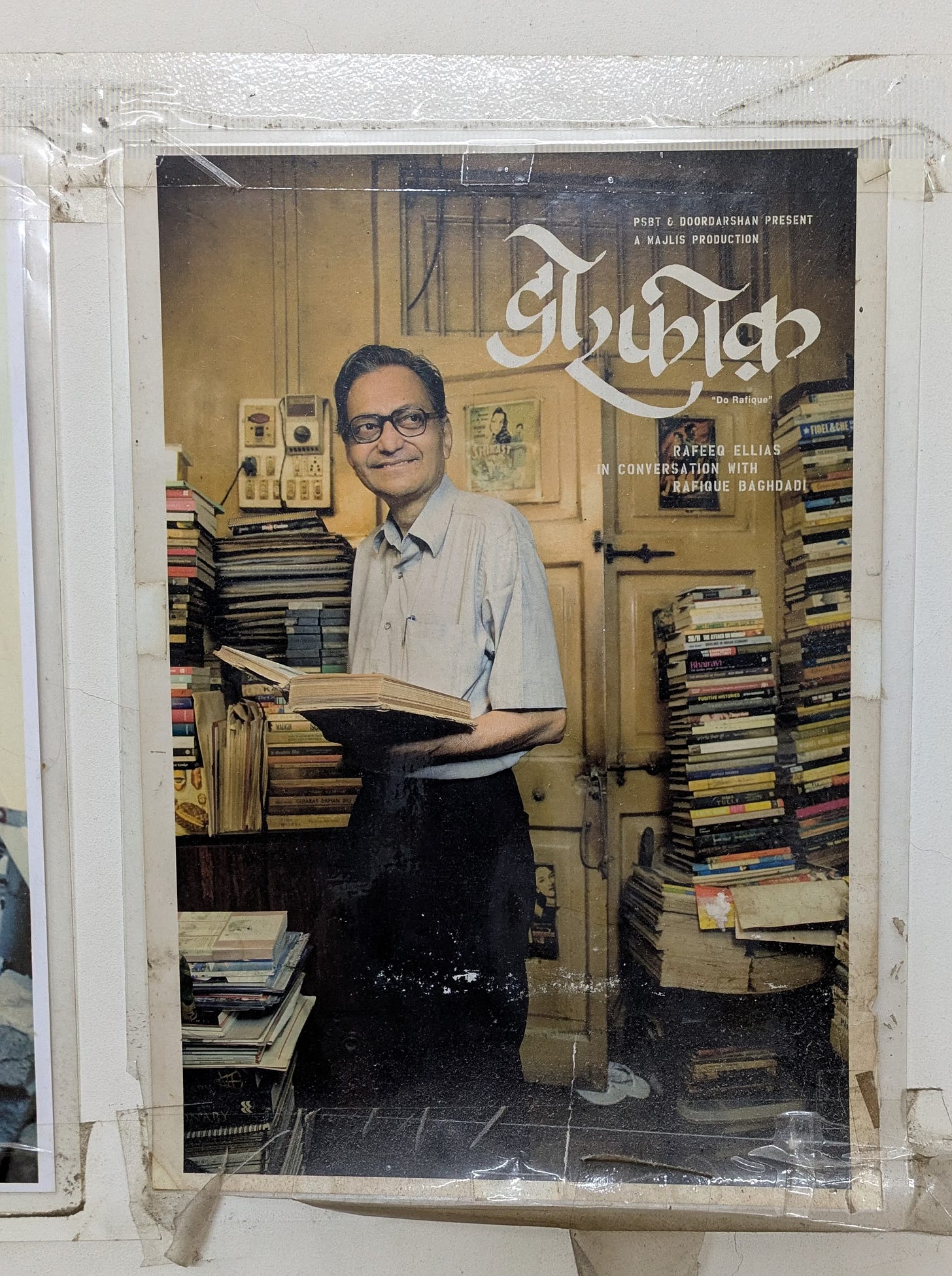

There, we read old magazines from the ’90s and were transported into another world. His walls were lined with books and DVDs. After I came home, I read a piece about him and discovered that this was the house he grew up in — he’d even turned his kitchen into a haven for books. And this man wanted to give us some of those treasured possessions.

We were complete strangers, and yet he welcomed us into his home, generously offering what he had, vulnerably, openly.

We talked for a long time — about books, about the film made on him — and eventually promised to return.

(Books I picked.)

I said I’d help him dust his books, and Uzma said that she’d read us a book while I cleaned. We all agreed on a book on food.

We walked out and went to a restaurant — they had tea and I had a meal. After that, Uzma and I walked to the base of Mazgaon Hill. The park at Mazgaon Hill was shut, so we walked back, completely bewildered by what a day we had, I mean, in the morning we had been strangers and now here we were bond by stories and connected to each other, having shared stories in a 100 year old house where Rafique had lived his whole life. Who would have thought!

When I came home, I googled, the story of the British woman who eloped. And guess where it lead me — Rafique. Here’s the piece from the Mint.

Elizabeth Draper, it says, was immortalized by the writer Laurence Sterne, whom she had met during a three-month stay in London in 1767. Sterne, the author of the popular humorous novel, The Life And Opinions Of Tristram Shandy, died of tuberculosis in 1768, but he kept up a steady correspondence with her through his illness, beseeching her to not return to India.

The story of Eliza Draper takes us back to 1772, when her husband, Daniel Draper, one of the East India Company’s senior-most officials in Bombay, arrived with her to live in Belvedere House, the manor atop the hill. “Back then, the sea was very close and the waters surrounded the hill. All the expanse of land you see today was reclaimed from the sea much later,” Baghdadi tells me. The sea’s erstwhile proximity is crucial to the story of Eliza Draper, who, at the young age of 25, decided to leave a stifling marriage of 10 years, and boarded the HMS Prudent one night. She reached Masulipatnam in Andhra Pradesh, where she briefly stayed with her uncle. From there she eventually reached London in 1774, where she published Sterne’s letters to her, titled Letters From Yorick To Eliza. Her new-found independence was short-lived. She died in Bristol, UK, in 1778, aged only 35. Today, the Bristol Cathedral contains a memorial to her, completed two years after her death by the sculptor John Bacon. The only sign of Eliza in Bombay is this headstone in Mazagaon covered by weeds and rubble. Belvedere House has long ceased to exist, its closest possible remnant being the road at the base of the hill that bears the same name.

Uzma and I kept texting. We couldn’t believe the kind of day we’d had — it felt surreal. The generosity of this man — who was vulnerable to call us home, yet kept steering the conversation back to books, films, and Bombay whenever it turned personal — stayed with us. It was nothing short of magic.

It made me believe that I should let life surprise me. So I’m going with that same thought for my book.

I’m meeting life with openness, and I have Rafique and today to thank for that. I couldn’t have imagined a day like today.

<3

Indu

love love love this, and fuck kindle india

What an amazing day! You have described it so well. Absolutely loved reading this. The books look super interesting.